What the heck is a Sequence, and does it really matter today?

- angelamrocchio

- May 24, 2024

- 17 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2024

Mass by candlelight at the Antwerp cathedral, by Flemish painter Pieter Neefs the Younger

A few months ago, a deacon was cleaning out some long neglected closets at church and came upon a small, dilapidated book of chants on the shelf. Knowing my interest in Gregorian chant, he gave it to me. The book was 100 years old (almost to the month!) and immediately piqued my interest, as it contained a number of unusual melodies for familiar chants, and on the flip side, entirely new texts for melodies I already knew and loved.

One of the chants which grabbed my attention was a sequence. It was identical to the Easter sequence...except that it had all the wrong words. I had never before encountered such an oddity. How was such a chant deemed appropriate to be included in what was clearly a well loved little book by a priest 100 years ago?

I'd like to say this whimsical story is the reason I decided to write this article. But honestly, the curiosity for sequences started many years earlier, and in a far less inviting manner. It began with a reader at Mass finishing the second reading per usual, but instead of leaving the ambo, she remained, and mumbled a strange poem that she didn't seem to understand. What was a random poem doing in the middle of the readings? And why didn't the priest seem to care? It was very confusing to me.

What the heck is a Sequence?

I love looking at the roots of words. Lots of people are intimidated by Latin because it's a foreign language. However, it's actually less foreign than one might suppose. In fact, 60 per cent of the English language is rooted in Latin. Example: Sequence is derived from the Latin word sequor (verb: to follow, come after) or sequens (adjective: next, following, subsequent).

So, what is the Sequence following? The Alleluia chant.

And here, friends, is where we start to see the source of our disconnect. In the modern western liturgy, the Sequence precedes the Alleluia, rather than follows it. Perhaps we should really call it the Non Sequitur, for it does not follow. For the sake of our little quest today, let us release the Sequence back into its native habitat, where it follows the Alleluia chant, that we may come to appreciate how this musical form came to be so incredibly popular that a golden age of sequences came to be, during which literally thousands were composed.

A bird's eye view: the medieval liturgy

Observe a parish music director today, and you'll likely discover a car seat covered with several binders of sheet music, one or two more bags full of more music, a pair of organ shoes, maybe an iPad (hopefully it will be fully charged), and an office with walls decorated in bookshelves and filing cabinets with — you guessed it, more music! A considerable portion of a music director's time is devoted to researching and programming repertoire appropriate to the denomination, the liturgical season or feast, the capabilities and interests of the choir members, musical leanings of the congregation and pastor, etc.

This is a far cry from the music of the medieval liturgy. There was no mix and match, no picking and choosing of music. There was one book of texts and melodies, and that's what all the musicians used. Today, a person might pine away for this simpler way of life, but this won't last long upon discovering that any time and energy saved in the planning department would have been redirected to learning the chants, which were anything but simple. To make matters worse, prior to the invention of the musical staff, all the music had to be learned and taught to others entirely by memory!

These predetermined chants all worked together, each with a unique compositional structure, intimately connected to its part of the liturgical whole. The Introit (entrance chant), for instance, moves through its syllables at a more or less metered pace, much like the procession of the priest and servers towards the altar at the very beginning of the Mass. The Gradual, in contrast, is highly melismatic, with sometimes thirty or more notes on a single syllable, leaving the listener the mental space and freedom to meditate on the words of the scriptural reading just proclaimed. The Alleluia, in turn, heightens a sense of expectancy, of which the proclamation of the Gospel is the pinnacle.

Thus, each chant in its own way played a crucial role in the development of the drama of the Liturgy of the Word.

"The Mass, despite the uncoordinated way in which it accumulated diverse elements over the centuries, is not merely a jigsaw puzzle of textual and musical elements. Long usage and familiarity created a unity that transcended the individuality of its parts. One must, furthermore, try to imagine the way the Latin liturgy might have been experienced by clergy and laity during the Middle Ages (or even up to the first half of the present century in Roman Catholic churches). Although the language barrier and the clericalization of the liturgy virtually excluded the laity from formal participation, a fervent belief that God became truly present on the altar transformed the experience for even the most unlettered worshipper. The richly decorated vestments, the comings and goings of the ministers and servers at the altar, the processions, the mystery of a sacred ritual language, the chanting and the silence, the glow of candles, and the fragrance of frequent censings created an encounter with the divine which powerfully united clergy and laity." — Joseph Dyer, The Medieval Mass and Its Music

Our story begins with the Alleluia jubilus: a wordless jubilation

A key characteristic of the Alleluia chant is the jubilus, a wordless jubilation, momentary departure from the text, and vocalization transcending the limitations of words and concepts. It occurs on the last syllable of the word Allelu - ia (- ya), an abbreviation of the unutterable Hebrew name for the Lord.

Alle (Hebrew Hallel) = Praise

Ya (Hebrew YHWH) = THE LORD

Here is a fairly modest example, chosen because of the sequence related to it, which we will discover shortly. (There are other alleluia chants with notated jubilii nearly twice as long as this one!)

Don't judge a book (of chants) by its cover.

Did you catch it earlier when I casually mentioned that all the liturgical melodies used to be memorized? Like, no big deal...right? Just kidding! It's a huge deal. For a Sunday Mass, there were at least five unique proper chants to be sung by the choir: easily 20 minutes of brand new music for one normal Sunday, not to mention all the other ordinary music which is repeated over and over for the season or for the whole year. It took seven years to memorize the entire liturgical repertory!

The ancients didn't have smartphones or notepads to make reminders. Paper was a very precious commodity, and most people didn't know how to read or write. It took a whole flock of sheep just to procure the parchment for a book. So, they developed the skill of memorization quite extensively. We're not sure exactly how they did it. We do know that they didn't have today's constant distractions of electronics, and they were much more mentally present to their surroundings than we are. (Hang with me here; I promise that all of this will relate back to sequences.)

The relationship of memorized music and notated music is incredibly complex:

The first musical notation did not indicate precise pitches, just directions (up or down) and a few dynamics. In an odd way, we can say that the first musical notation does not actually provide any notes at all!

Not every part of every memorized melody was actually written down.

Books were in short supply, and copied by hand. Copyists were human, and they did occasionally make errors.

There is an often overlooked aspect of early music called the Oral Tradition. It does not live in books, but was passed down to future generations as a lived experience.

Neuma, i.e. complex, formulaic melodies, were memorized by singers and interpolated within existing written melodies.

There was a time when improvisation played an important role in all music, including liturgical singing.

Now, what is important to know here, is that the jubilus of the Alleluia chant tended to be much longer than what was actually notated in manuscripts and handed down to us.

"The reading of the Epistle being ended, the “Gradual" and “Alleluia" were chanted; during which, to add dignity to the reading of the Gospel, which in all Churches, east and west, was distinguished by all available pomp, a procession was formed, consisting, according to Sarum use, of the deacon bearing the “text," [book of the four Gospels, beautifully bound] preceded by a thurifer, candle bearer, and cross-bearer, and the subdeacon carrying the book out of which the deacon was to read the Gospel. The passage of the procession from the altar, and its ascension to the pulpit or rood-loft, occupied some minutes, and, to avoid a break in the chanting between the Alleluia and the Gospel, the final "a" of the Alleluia was prolonged by a run or cadence, called a "Neuma," extending sometimes to nearly a hundred notes. This was both unmeaning in itself and difficult to retain in the memory, but it continued practically unaltered for some three hundred years, and was in fact the Sequence, Sequentia, properly so called." — Charles Buchanan Pearson, Sequences from the Sarum Missal

What we singers owe to a 9th century monk with a speech impediment

It's time to introduce you to a friend with a rather unfortunate name. Notker (c. 840-912), was a Benedictine monk living at the famous Saint Gall Abbey not long after the death of Charlemagne. As a youngster he struggled with speech impediments, including a stutter, and to this day he is known as Notker the Stammerer. In spite of physical ailments, he became a scholar, teacher, and poet.

Brilliant Notker had a bit of a problem, however. He had trouble memorizing the "very long melodies" of the liturgical chants. When he came upon a book of chants with sequences set to verses, he realized he had in his hands the makings of a possible solution. If he could take these longissimae melodiae and set them to words, they would be easier to remember!

The task was not to be undertaken lightly. We have already observed how carefully the chants of the liturgy were laid out by the time Notker arrived on the scene. Unlike today, it wasn't possible simply to change the words, or to substitute a different chant that he liked better.

Notker had to work with what the Church had already provided:

the pre-existing melody of the jubilus (including any unwritten extensions — like the ones he had such a hard time memorizing), which was different every Sunday and every feast day

the sense of crescendo to the pinnacle of the Liturgy of the Word: the Gospel

unity with the rest of the liturgical organism

the theme of the day's feast or the liturgical season

the use of Latin, the official language of the Roman Church

this should go without saying, but I'll say it anyway: it must be theologically sound

With much encouragement by his mentors, what Notker ultimately devised, he published in a book called the Liber Hymnorum (not to be confused with the unrelated Liber Hymnarium). This book contained 33 distinct Sequence melodies and 40 Sequence texts.

Now, if you just played word sleuth as I like to do, and surmised that Liber Hymnorum means Book of Hymns, then you did very well. And, of course, this leads to another disconnect which we must sort out, because in this circumstance, Sequence and Hymn do not in fact mean precisely the same thing. A Hymn is a single melody which repeats over and over again, with different metrical texts on a theme fitted to the one melody. Sometimes there is a second melody with one single text added to the first one, called a refrain. But that's about it.

A Sequence, on the other hand, can utilize all sorts of melodies of varying lengths. Most of them are repeated once before moving on to the next in a fundamental principle called "progressive repetition".

The mission of the International Chant Academy is to keep the beauty and meaningfulness of Gregorian Chant and Early Sacred Music alive and relevant. We foster understanding of these art forms, and teach the musical and vocal skills necessary to excellent performance.

Visit our website.

Of the four (or five) sequences still in universal use today in the western Church, here are the structures [with brackets around breaks in the patterns]. You may click on the links to hear and see them in chant notation, if you wish:

Victimae Paschali Laudes (Easter): 1 2a 2b 3a 3b 4

Veni Sancte Spiritus (Pentecost): 1a 1b 2a 2b 3a 3b 4a 4b 5a 5b

Lauda Sion (Corpus Christi) 1a 1b 2a 2b [3a 4a 3b 4b] 5a 5b 6a 6b 7a 7b 8a 8b 9a 9b 10a 10b (*11a 11b 12a 12b) *shortened form, Ecce Panis Angelorum

Stabat Mater (Our Lady of Sorrows, Sept. 15): 1a 1b 2a 2b 3a 3b 4a 4b 5a 5b 6a 6b 7a 7b 8a 8b 9a 9b 10a 10b

Dies Irae (All Souls, and Requiem Masses): 1a 1b 2a 2b 3a 3b 1c 1d 2c 2d 3c 3d 1e 1f 2e 2f [3e 4 5 6] Amen

I'm skipping ahead a few centuries, however. Notker did not pen any of these timeless gems. They come from a later period, when the Sequence had grown into an independent musical form distinct from the jubilus of the Alleluia chant. We still have him to thank for them, because it is due to his Liber Hymnorum that this brand new form of the Hymn-Sequence gained the attention of the Church.

Notker's Sequence Psallat ecclesia

Let's go back for a moment to the Alleluia jubilus and its longessimae melodiae of 100 notes or more. After much trial and error, our monk friend landed upon what he said was the first representation of the perfection of his attempts: the sequence Psallat ecclesia. The sequence was written to align with the repetition of an alleluia of Adventide: Alleluia laetatus sum.

Notker's Latin text (which was edited many times over ensuing centuries, so we don't know exactly what all the original words were) went something like what you will find below. (Here's sheet music for Alleluia laetatus sum, sans sequence, if you'd like to follow along.)

Psallat ecclesia mater illibata et virgo sine ruga honorem hujus ecclesiae

May the Church, mother inviolate and virgin unwrinkled, sing songs to the honor of this church.

Haec domus aulae caelestis probatur particeps

May this house be found a partner with the celestial halls,

In laude regis caelorum et cerimoniis

In praise and worship of the king of heaven

Et lumine continuo aemulans civitatem sine tenebris

Emulating by its perpetual light that city without shadow,

Et corpora in gremio confovens animarum quae in caelo vivunt

And sheltering in its bosom the bodies whose souls live in heaven.

Quam dextra protegat Dei

May the right hand of God protect her,

Ad laudem ipsius diu

To his everlasting praise!

Hic novam prolem gratia parturit foecunda spiritu sancto

Here may grace bring forth new offspring, made fruitful by the Holy Spirit.

Angeli cives visitant hic suos et corpus sumitur Jesu

Here may the angels visit her residents, and here may the body of Jesus be consumed.

Fugiunt universa corpori nocua

May all things hurtful to the body flee away!

Pereunt peccatoris animae crimina

May the wrongs of the sinful soul perish!

Hic vox laetitiae personat

May the voice of gladness here resound!

Hic pax et gaudia redundant

May peace and joy here abound!

Hac domo trinitati laus et gloria semper resultant

May the praise and glory of the Trinity always echo in this house!

The English translation of Psallat ecclesia (with the exception of three lines) is by Richard Crocker, as found in his book, The Early Medieval Sequence.

The structure of Psallat ecclesia: 1 2a 2b 3a 3b 4a 4b 5a 5b 6a 6b 7a 7b 8

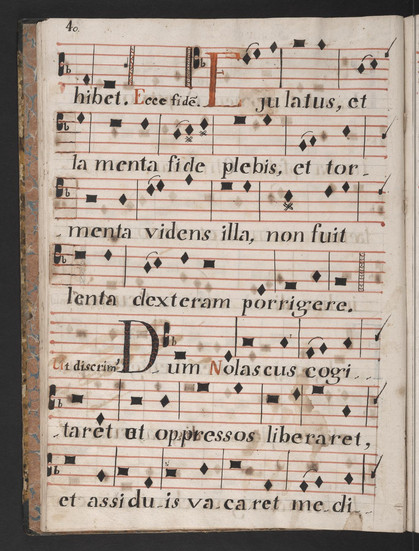

Psallat mater ecclesia, sequence for the dedication of a church, from a 15th century Sequentiarum, or book of sequences (shelfmark NL-Uu : Hs. 0415 in the Cantus Index)

This sequence was written "In Dedicatione ecclesia" (for the Dedication of a church). The theme flows naturally from the text of the Alleluia verse just preceding it, Psalm 121:1: I rejoiced when it was said unto me: "Let us go to the house of the Lord!" Here we gain a glimpse into the theological nature of the Sequence.

"[The previously existing ordinary and proper chants of the Mass] formed the foundation upon which an edifice of an entirely different sort of chant was built: the non-scriptural chants of newly invented text and melody, which were added by way of expansion and elaboration to the original corpus—Tropes and Sequences. Their function is that of adding new comment to the old pieces. Their texts are highly imaginative, showing a marked contrast to the psalms; their meters and rhymes are sometimes intricate and elaborate, sometimes obvious and forceful. They are much more earthbound and belong more characteristically to a specific medieval literary culture; they provided a timely balance and commentary to the more timeless, stable elements of the liturgy." — William Mahrt, The Musical Shape of the Liturgy

The Golden Age (and subsequent decline) of Sequences

The centuries sequens Notker (forgive me, I couldn't resist the pun) saw a considerable expansion in the work begun by him. Once his compositions were incorporated into the Mass, others followed suit, composing their own poems for liturgical use as he had. In Paris, during the twelfth century, another brilliant poet, theologian and composer by the name of Adam de St. Victor took the musical form to new heights. Adam reduced the Sequence to a much more polished and rhythmical form. 47 of his sequences survive to this day (not to mention the rest of his original hymns still in use). His achievements ushered in the golden age of Sequences (12th-15th c.) during which another 3,000 sequences were penned.

At some point, the Sequence developed into a completely independent musical form, though generally still related to its preceding Alleluia. Thus, four of the five sequences in use today are in the same mode as their preceding alleluia's (the one exception is Victimae Paschali Laudes in Mode I, with Alleluia pascha nostrum in Mode VII). Sequence melodies, like hymn tunes, were given their own names, and were sometimes repurposed many times with different texts. For instance, when Thomas Aquinas composed Lauda Sion, he framed it to an existing sequence melody, Laetabundi iubilemus, composed by Adam de St. Victor. The same melody has been used numerous times in other sequence texts, including Profitentes Trinitatem for the Holy Trinity and Gaudeamus exultantes for the Sacred Heart.

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) took on many reforms of the Roman liturgy, and in the process, retained just four sequences (Stabat Mater was re-introduced later) in the Roman Missal. The Sequence, being a later addition to the liturgical repertory, by nature a poem and not a scriptural text (most of the other proper chants are taken from scripture), and in usage varying greatly from region to region (as one must surmise, given the thousands of sequences in circulation), it was decided at the Council not to be of the same caliber and importance as the rest of the propers. The few which were kept were so well loved due to their superior artistic and theological merit, that it would have been a crime to omit them.

The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) further reformed the Sequence by making only two, Victimae Paschali Laudes and Veni Sancte Spiritus mandatory, by removing Dies Irae from the Mass entirely, by proposing an optional shorter version Ecce Panis Angelorum to the already optional Lauda Sion, and by moving all sequences before the Alleluia.

Certain religious orders retained for their own use sequences pertaining to their respective charisms and saints. For example,

Benedictine: Laeta dies magni ducis (St. Benedict, July 11)

Carmelite: Flos carmeli (St. Simon Stock, May 16)

Dominican: In caelesti hierarchia (St. Dominic, August 8)

Franciscan: Sanctitatis nova signa (St. Francis of Assisi, October 4)

Mercedarian: Laudat agmen captivorum (Our Lady of Ransom/Mercy, September 24)

Does the Sequence really matter today?

I'll be perfectly honest. While researching this article, I had a crippling attack of skepticism. Perhaps some of these same thoughts occurred to you, too.

Gospel processions aren't as elaborate today as they were in the golden age of sequences. There isn't time to get through a jubilus of 100 notes, let alone a long sequence.

Most churches don't sing the elaborate Alleluia chants on which the Sequences are based, so there would be an artistic disconnect moving from a long, modal sequence into a short, repetitive "gospel acclamation".

The artistry of the Latin language is lost in translation to the vernacular. (Latin is a highly poetic language in its own right.) It is nearly impossible to reconstruct in another language a text of similar meaning and poetic meter as the original language. So, either we will end up using the original Gregorian melody with a clunky English translation, or we must dispense with the Gregorian melody altogether.

A new approach?

The ICA draws readers from many different backgrounds, and as a general philosophy I do not believe there is a cookie cutter, one-size-fits-all approach. My primary experience is in the modern Roman Catholic liturgy, and having been blessed to work with many of our Protestant brethren through the ICA, I am aware that there is quite a bit of liturgical borrowing that happens between denominations.

So, take what you like from what follows, and leave the rest.

First of all, however you approach the Sequence, please, be intentional about it. It's not a poem that everyone forgets about til 5 minutes before Mass starts. If it is treated as an integral part of the liturgy, and planned around in that manner, it is more likely to be experienced in that manner. The Sequence and the Alleluia are integrally related, and should be treated as such. This could look like singing a sequence, followed by a bit of organ fanfare and a modulation into the key of the alleluia while the gospel procession begins. Or it could mean taking the time to choose an alleluia in the range and key (and grandeur) of the sequence. Here, I must give a plug for Dr. Horst Buchholz' Easter Alleluia, which provides a lovely segue with both the Easter and Pentecost sequences.

Worship aids are great, because you can print lyrics and translations!

Next, if your choir isn't ready for a full-blown Gregorian Alleluia, perhaps you can meet them in the middle. Sing the alleluia with jubilus, and the verse according to a modal psalm tone. The Liber Brevior actually has a section with full Alleluia chants and simple tone Latin verses, starting on p. [2] (after p. 640).

The Nova Organi Harmonia has the full Gregorian Alleluia chants in standard notation, with accompaniment.

The "progressive repetition" which is integral to the form of the Sequence lends itself to musical contrast. The first iteration can be a cappella by a cantor or the choir in unison, and the second iteration with organ and full choir/harmony. Some polyphonic settings have been penned which play with this duplex form as well.

Most of the motets and anthems learned by choirs these days have fairly general themes. Sequences, in contrast, are composed for very particular feasts and Sundays, providing extremely rich sources for meditation and theological reflection. Sequences don't have to be programmed as sequences. There is no reason not to plan them as "other suitable music" for the offertory or communion.

So, I repeat my question: Does the Sequence really matter today? Even if you never devote another brain cell to the planning of sequences ever again, you've devoted this time to reading a blog article about Sequences, and challenged yourself to think about liturgy and music from a different perspective.

That alone is a "win" in my book! Thank you for joining me and listening to what I have to say. :-)

While you are here, a few honorable mentions...

Ave Maria virgo serena

Josquin's gorgeous polyphonic work by this title is still popular today, but most don't know it is actually based on a chanted sequence.

Gaudeamus exultantes (for the Sacred Heart)

Uses the same melody as Lauda Sion for Corpus Christi.

English translation pp. 164-165

Laudat agmen captivorum (to Our Lady of Mercy)

A conversation in an internet forum suggested that the Mercedarian order has their own sequence, so a hunt naturally ensued on my end. The Mercedarians were founded in 1218 and are devoted to Our Lady of Mercy. I could not find a printed copy of the sequence anywhere, but I did find an old 17th c. Spanish gradual which contains the Mercedarian propers (the sequence is pp. 39-43; the first two pages are below), and a single YouTube video with a version in English, sung to a tune similar to Ave maris stella. The English text is in the caption to the video.

Profitentes Trinitatem (to the Holy Trinity)

Uses the same melody as Lauda Sion for Corpus Christi.

Scrupulosa Quorundam Sententia

Sequence for Saint Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins

Virginis Mariae laudes

Based on Victimae paschali laudes for Easter, this is the piece that triggered the writing of this blog article. The book in which I found it suggests it be sung "au temps pascal" (during the Easter season), but the original manuscripts suggest it was connected to the celebration of the birth of Mary, and that it is appropriate in general for feasts of Our Lady.

sheet music with English translation (updated 9/16/24)

Two sequences by Hildegard von Bingen

O virga ac diadema for the Virgin

O ignis Spiritus paracliti for the Holy Spirit

And I haven't even touched on polyphonic settings of sequences....another blog article in the future, perhaps?

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up for our email newsletters to receive our latest blog posts and other items of interest. You'll pick how often to hear from us.